With rising health costs and higher health care needs on the horizon, Canadian health care systems need to start thinking about ways to keep people healthy in their communities and out of hospitals. This will take an herculean effort of change, one that will require health care planners and policy-makers to make some difficult choices on how to orient financial and healthcare human resources.

Fortunately, we are getting a better handle on what really makes people sick.

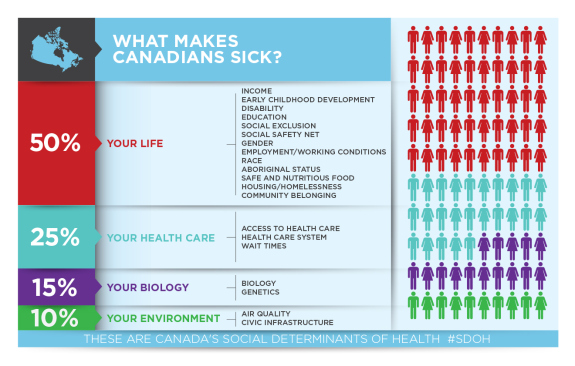

When assessing health needs from a population health perspective, health care has a moderate impact in how healthy we are. The Canadian Medical Association reports that, actually, health care only accounts for 25% of our health status, and that up to 50% is dependent on our access to social and economic resources, or the upstream factors that influence our health.

This doesn’t mean that health care is off the hook, however. It means that those in the health care system, in fact, will have to lead the charge in redefining what it means to helping communities to stay healthy.

Ironically, as proud as Canadians are of our health care system, upstream thinking is already having a unexpected innovative renaissance elsewhere, south of the border. The efforts made in the United States may provide a spark to expand the current scope of health care in Canada, beyond hospitals and into helping communities have the resources to maintain health.

Inspiration from upstream investments in the United States:

American health systems (hospitals, networks and insurers) are beginning to realize that investing in patients’ social and economic needs may be the key of lowering their costs. The following are a few examples of upstream thinking in health care.

A lot of work has been happening recently around Medicare insurance expanding to cover non-clinical expenses. For example, Hawaii now allows Medicare expenses to help homeless clients receive housing. Specifically, Medicare dollars will be available to cover costs of transportation and job training-related expenses to acquiring affordable housing. Though it does not yet cover rent or utilities, the Lt. Gov. of Hawaii is hopeful it will happen.

Large hospital networks are also seeing the value in investing in the social determinants of health for their patients. Kaiser Permanente are investing 200 million dollars towards housing, recognizing too that health is created primarily at home, outside of the traditional clinics. They have announced three investments: The purchase an East Oakland apartment complex dedicated to keeping rent low, a $50 million dollar fund to preserve existing affordable housing, and an initiative to find housing for over 500 people in Oakland who are above 50, homeless and have one or more chronic condition.

Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvanian demonstrates upstream action by investing in healthy food for their high-risk diabetic patients and showing that an average investment of $2,400 per patient on healthy foods lead to an 80% decrease in average health expenditures – from $240,000 to $48,000 per patient. The “farmacy” as they call it has given them the opportunity to think about health care differently, allowing a “non-traditional” intervention that has demonstrated both health and economic value to inform their practice.

What are the lessons?

While solution will need to be tailored to work within universal health care system framework in Canada, the American initiatives provide examples of out-of-the-box targets that health care decision-makers can consider. These efforts demonstrate that hospitals, medications and therapies are not the only ways a health care system can help citizens stay healthy.

Mobilizing solutions will firstly take a dedication to actively understanding the clinical and non-clinical needs of the communities. It will also take the willingness of decision-makers to have broad perspective of what provides real value to communities, and a re-imagining of what a health care system ought to be good for.

In the end, any public system ought to be optimizing the public good. In health care, we are realizing that optimal population health starts with investing in people, and with some creativity, the future of health care will depend on our ability to think upstream.