— Edward Saperia (@edsaperia) November 30, 2018

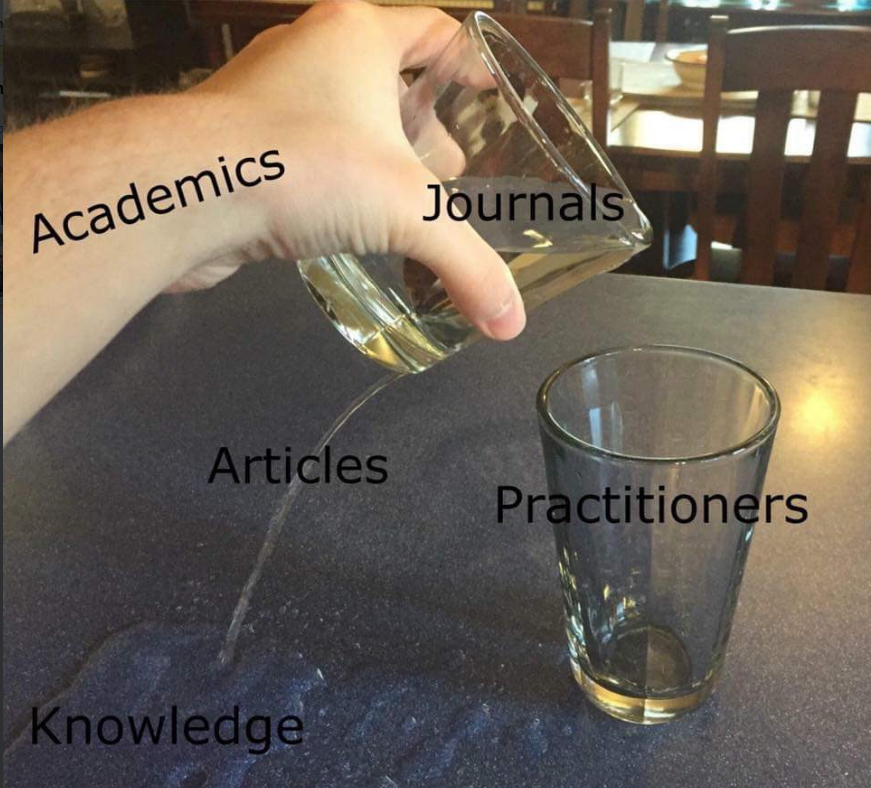

A meme after my own heart….

The evidence-practice gap is not news. In health care, 17 years is the often cited period of time it takes for evidence to become medical practice. The truth is, however, we might not actually know how long this lag exactly is….

What we do know is that the smaller the gap, the better off patients will be.

My experience in both sides of the aisle – academia and inside a health system – have given me the following insights on this problem:

- Practitioners involvement is inconsistent:

The Canadian Institutes for Health Research recommends that “integrated knowledge translation” – involving practitioners in the research process – is a way to remedy the evidence-policy gap. Unfortunately, the i-KT approach is “challenging and inconsistently applied“. For example. in my opinion, you have to submerge yourself in the data of your research to fully appreciate the problem you are trying to solve. This is of course, time intensive, and therefore, in many cases, practitioners can not be involved in getting their hands dirty. It is then a big mistake to believe that integrated-Knowledge Translation is the panacea to our implementation woes, without being specific about what meaningful involvement looks like. - Academic knowledge lacks context, frustrates end-users:

Each health care system has their own contextual features to consider when tackling a systemic problem. Academic knowledge about addressing systemic issues, on the other hand, is often presented in a context-free manner, largely due to the fact that journal articles are too short to provide any meaningful context about the setting a problem had been already solved in. When a decision-maker is then presented with context-free information, it is easy for he/she to start looking for reasons why this knowledge does not apply to their setting, rather than looking for commonalities. - Practitioners need good sounding ideas, communicate clear value:

Say an eager policy entrepreneur in an organization finds what he/she thinks is the evidence behind a good idea. What should they do next?

There is very little attention being paid to the fact that, actually, a new policy or programmatic ideas has to be sold to leadership in an institution. This step takes creativity and savvy convincing skills on behalf of the policy entrepreneur. I would argue that to help this hypothetical person, we need to find a better way to transform validated results from health system-research into information that communicates patient and system level value, in person-first language that is easier to understand than statistics. Policy-briefs are one step towards this kind of work, but we can definitely do better….

It is heartening to see a surge in research into implementation-related questions (check out Implementation Science). I do fear, however, that tackling the implementation questions in the same esoteric way as every other problem may leave us with a puddle of answers to the question of how to better answer questions, slowly dribbling farther away from those who are thirsty for solutions.